I launched this newsletter and then promptly fell into a hole of grading: I’ve marked nearly 70 term papers and 70 handwritten essay exams, with a few more to finish up by the end of the week.

In spare moments, though, I finished Kathryn Lawson’s fascinating book Ecological Ethics and the Philosophy of Simone Weil: Decreation for the Anthropocene (2024) and also read Robin Wall Kimmerer’s The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World (2024). In a delightful synchronicity, Lawson cites Kimmerer’s earlier book Braiding Sweetgrass, which I loved—in fact, as I was reading, I jotted “Kimmerer?” in the margin, only to find her cited just a paragraph later. These webs of citation and influence always delight me (more on this theme below).

Lawson’s book cites a wide range of philosophers both ancient and contemporary (Plato is a key player), as well as postmodern theologians, Weil scholars, deep ecologists, and theorists of the Anthropocene, a term sometimes used to describe our current geologic era of amplified human affect on climate and the environment. At the end, she also gives examples of artists and activists who enact some of the book’s ideas. Lawson shows how Simone Weil’s writing can offer wisdom for this moment:

"Her work has an ability to hold open an absolute love of the earth alongside the existential despair that living upon the earth so often entails. This seems absolutely necessary for thinking through the terrifying prospects of extinction and destruction while still trying to live one's life. Her ability to unflinchingly note the absurdity, loss, and suffering of existence while still performing loving actions in the world is necessary for thinking through the environmental catastrophes faced by this planet.” (2)

Lawson especially considers Weil’s concept of decreation:

"while decreation is traditionally read by Weil scholars as the act of self-abnegation alone, I have included the recreation of the self as relational as a necessary aspect of decreation. The process of decreation produces a relational self who is not egoistic but has an 'ecstatic' embodied awareness of the self's very existence being entwined, even co-created, within a broader 'ecology' of others. Action marks the second, creative movement of decreation." (4)

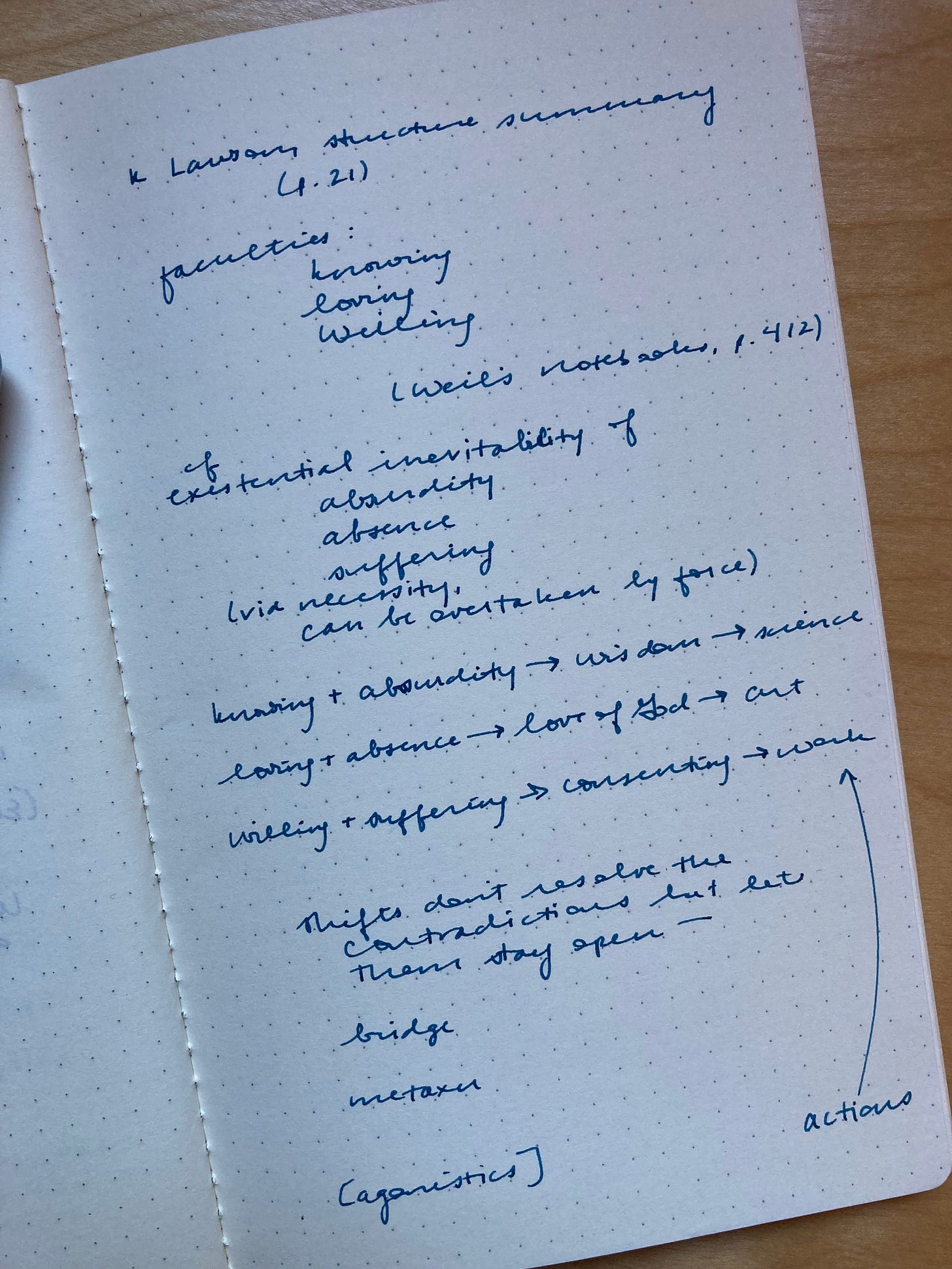

The book goes into much more philosophical detail than I’m outlining here (as my notes above highlight), but a general premise is that we need to build our capacity to pay attention to what is wrong in the world and our capacity to ethically respond, even when that response is costly and risky and has no guaranteed outcome. I’ve thought for a long time that Weil’s relevance to climate action is in part her implicit agonism—her insistence on holding open irresolvable tensions—and so it was gratifying to see Lawson explicitly use the language of agonistics to write about Weil. (I gesture toward these dynamics in the conclusion to The Literary Afterlives of Simone Weil.) I hope many readers will find Lawson’s book, which initiates a compelling application of Weil’s wisdom for our world:

“If we love the earth's beings and know our interconnection with said beings, we consent to continue, to work against the odds for ethical action. We consent to the imperfection of our world and our work. We consent to reality in all of its necessity and suffering, but we do not consent to accepting it fatalistically. Instead we find balance between love and suffering and to ease the affliction of others." (174)

Extending the topic of interconnection, Kimmerer’s book is a brief and lovely illustrated meditation on the wisdom of the serviceberry—or the Juneberry, or, where I live, the Saskatoon berry. Kimmerer draws our attention to the Saskatoon as an exemplar of the gift economy, in contrast to the individualistic accumulation (hoarding?) encouraged by our current capitalist system. As always, she interprets the natural world as both an environmental biologist and a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, seeking to spark our imaginations of the reciprocity and grace-filled abundance and mutual care we can learn from the plants and animals around us.

Kimmerer does not cite Weil, but I hear a quiet conversation between the two writers. Kimmerer writes, “Recognizing ‘enoughness’ is a radical act in an economy that is always urging us to consume more” (12), reminding me of Weil’s writings on decreation. Although some commentators interpret this concept as a kind of toxic self-erasure, with Lawson, I understand it as a self-limiting that makes room for others. Kimmerer goes on, “Imagine the outcome if we each took only enough, rather than far more than our share. The wealth and security we seem to crave could be met by sharing what we have” (12).

As in Weil, Kimmerer’s vision of self-limitation for the sake of others arises not just from duty but also love. Kimmerer writes of the accountability and happiness that result when we find ourselves in relationships of reciprocity: the berries aren’t just nourishing, they’re delicious. Her book is full of stories about sharing and participation in the common good: neighbours’ berry farms, Little Free Libraries, traditional library cards, roadside stands. She centres communities of persistence and practices of gratitude, and I hope to return to these themes in future writing.

For now, let me say that one more gift that emerged from these two books was the nudge to read another book that’s been on my shelves for a while: Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s 2015 book The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. If you’ve read this book, I’d love to hear what you think of it! Lawson cites Tsing repeatedly, and I found myself marking every quotation and also remembering another writer who had enthused about Tsing’s book recently, namely Ross Gay in The Book of (More) Delights. (Ross Gay, incidentally, also cites Kimmerer in this collection.) I’m on the record as a deep admirer of Gay’s work, too, so the double recommendation is a strong pull. I plan to report back.

These webs of generosity—the generosity of citation, of recommendation, of conversation and cross-pollination—are the gift economy of my line of work, I think, and I love the way they thread themselves into such beautiful patterns through words, paper, thought, minds, and the discipline of attention (there’s Weil again).

And here’s Tsing, via Lawson:

"In order to survive, we need help, and help is always the service of another, with or without intent. When I sprain my ankle, a stout stick may help me walk, and I enlist its assistance. I am now an encounter in motion, a woman-and-stick. It is hard for me to imagine any challenge I might face without soliciting the assistance of others, human and non-human. It is unself-conscious privilege that allows us to fantasize—counterfactually—that we each survive alone." (143)

It turns out, again and again, that the way we survive is together.

Thank you so much for thinking with my book, Cynthia! I look forward to continuing these conversations with you!

I’m so glad you started writing here!